BORROMEAN RINGS

+-----+

| |

+-----+ |

| | | |

| +-|---+ |

| | | | | |

| | +-|---+

| | | |

+-|---+ |

| |

+-----+

Description: Gaby (@gabyjidom) and I have started going to a silversmithing course with a family friend, Marco, who has been kind enough to show us the basic principles and techniques behind creating silver jewlery. We’ve now reached that point at which we’re supposed to be planning and executing our own projects, and, for a while now, I’ve been wanting to build a ring with the form of a Borromean ring. It turns out that doing this actually has a fair degree of mathematical sophistication, and, since I’ve not found any good on-line resources on how to do this, I’d like to document some of the reasoning behind it.

Borromean Rings

According to their Wikipedia entry, the Borromean rings are “three simple closed curves in three-dimensional space that are topologically linked and cannot be separated from each other, but that break apart into two unknotted and unlinked loops when any one of the three is cut or removed”.

Apart from their natural mathematical relevance, they are culturally important: they are “named after the Italian House of Borromeo, who used the circular form of these rings as a coat of arms, but designs based on the Borromean rings have been used in many cultures, including by the Norsemen and in Japan. They have been used in Christian symbolism as a sign of the Trinity, and in modern commerce as the logo of Ballantine beer, giving them the alternative name Ballantine rings.”

They are also relevant to other fields of study: for instance, “physical instances of the Borromean rings have been made from linked DNA or other molecules, and they have analogues in the Efimov state and Borromean nuclei, both of which have three components bound to each other although no two of them are bound”.

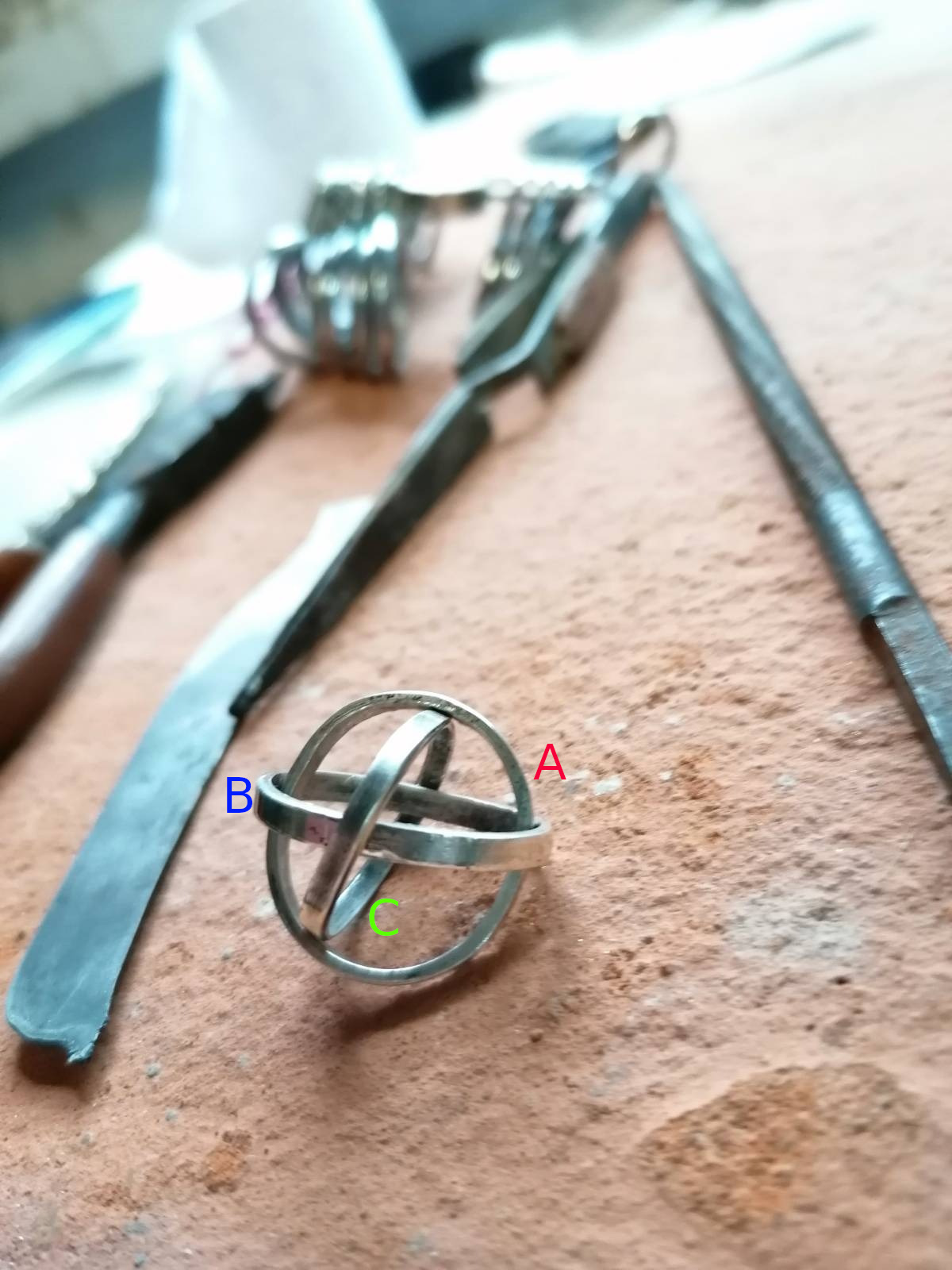

To understand how it is possible that the Borromean rings are unknotted when one of the rings is removed 1, I like to think of them as a violation to a sort of transitivity; that is, if we have rings A, B and C. We can “make” them “Borromean” if we think of A being “within” B and B “within” C, but C “within” A. Clearly, here we’re violating the transitivity of whatever “within” means. This can perhaps be better understood by looking at the following photo of the first prototype I could build of them:

One can notice that such relation with much more clarity:

A ──────────┐

▲ ▼

│ B

│ │

└──── C ◄────┘

Borromean Rings Ring

To be able to construct a ring (as in jewlery 💍) out of some Borromean rings, it is important not only to break transitivity, but also to note that the following conditions cannot be satisfied simultaneously:

a) The rings are of the same size.

b) The rings are perfectly circular.

The reason they cannot be satisfied simultaneously is because if the rings are perfectly circular and of the same size they would not fit “within” each other 2. In other words, circular Borromean rings are actually an example of an impossible object. Therefore, if we want the rings to be of the same size (which we do), we’ll have to shape them as ellipses, with an arbitrarily small eccentricity.

This means that, in order to fit a “Borromean rings ring” to a given ring size 3, we’ll have to calculate the circumference of the ellipses that will compose it, which will be, of course, strictly greater than the usual circumference for that given ring size.

Calculating the ellipses

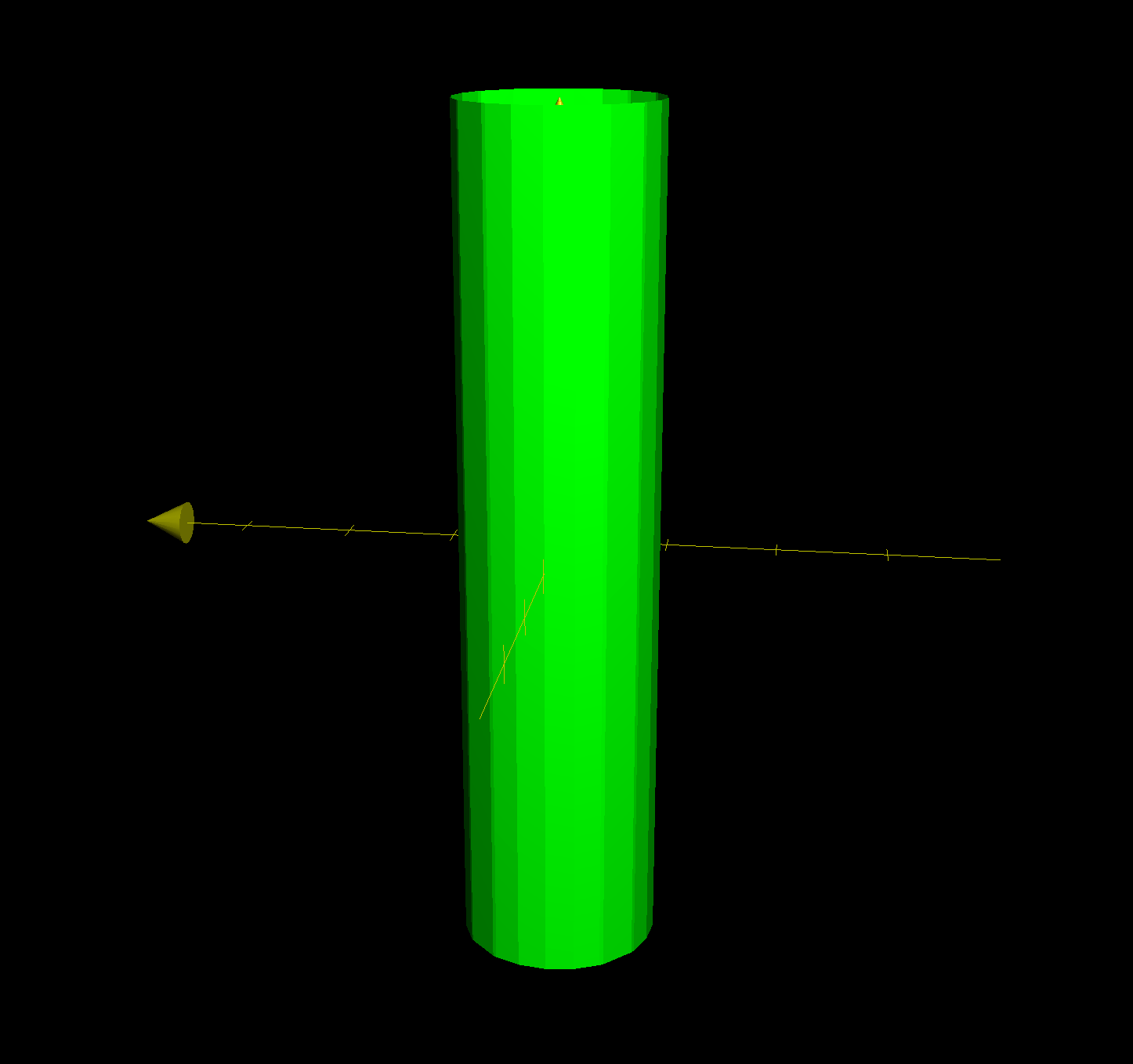

To understand how we’re going to calculate the ellipses, imagine that we have a finger represented by a cylinder, given by the following equation:

\[\frac{x^2}{r^2} + \frac{y^2}{r^2} = 1\]Such cylinder looks a bit like this:

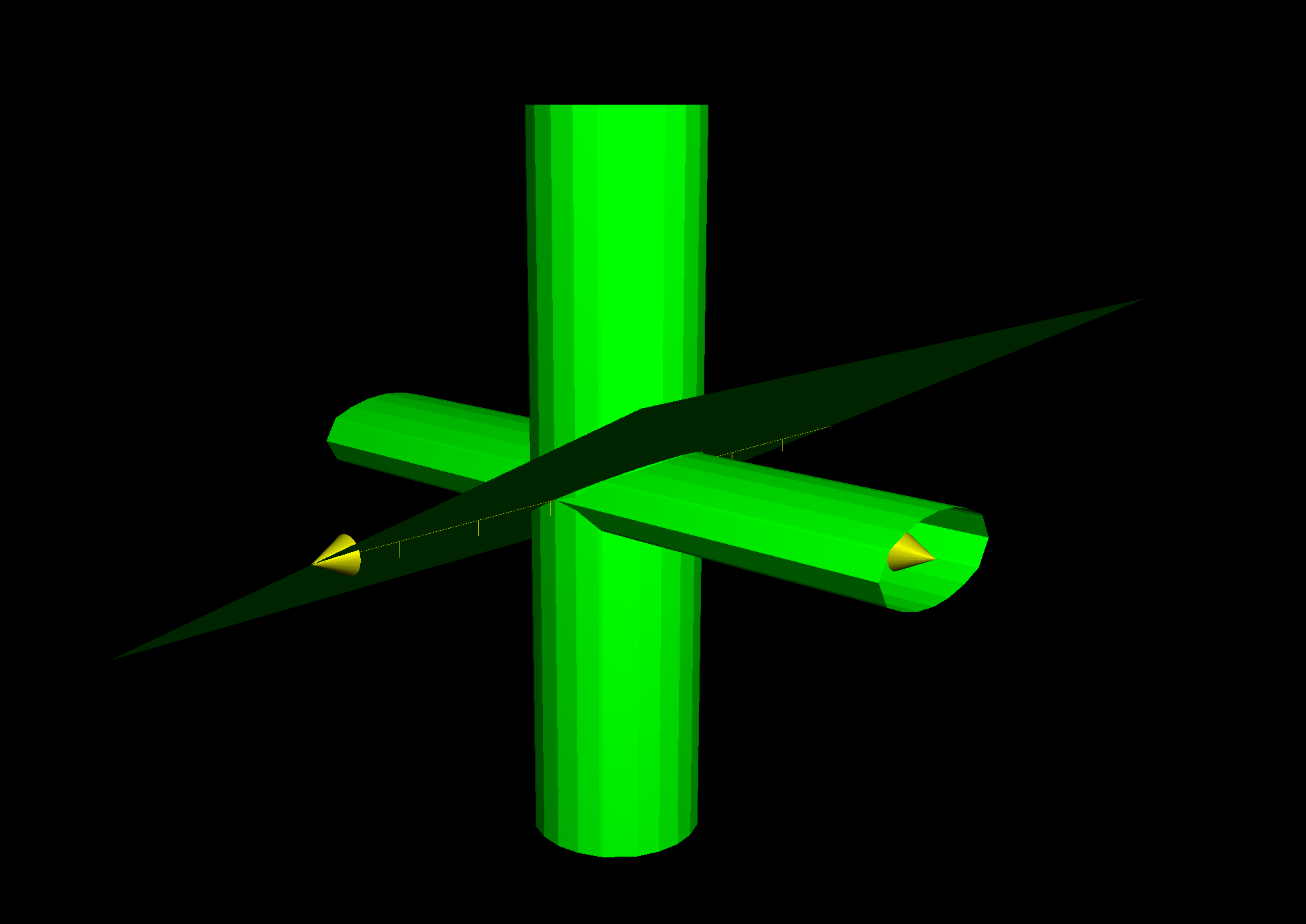

Note that, given the shape of the Borromean rings, the way way the finger goes through them is a bit like this:

That is, each ring is positioned at an angle within the range of \([\frac{\pi}{8}, \frac{\pi}{4}]\) ([22.5°, 45°]) quoad the axis that is perpendicular to the finger.

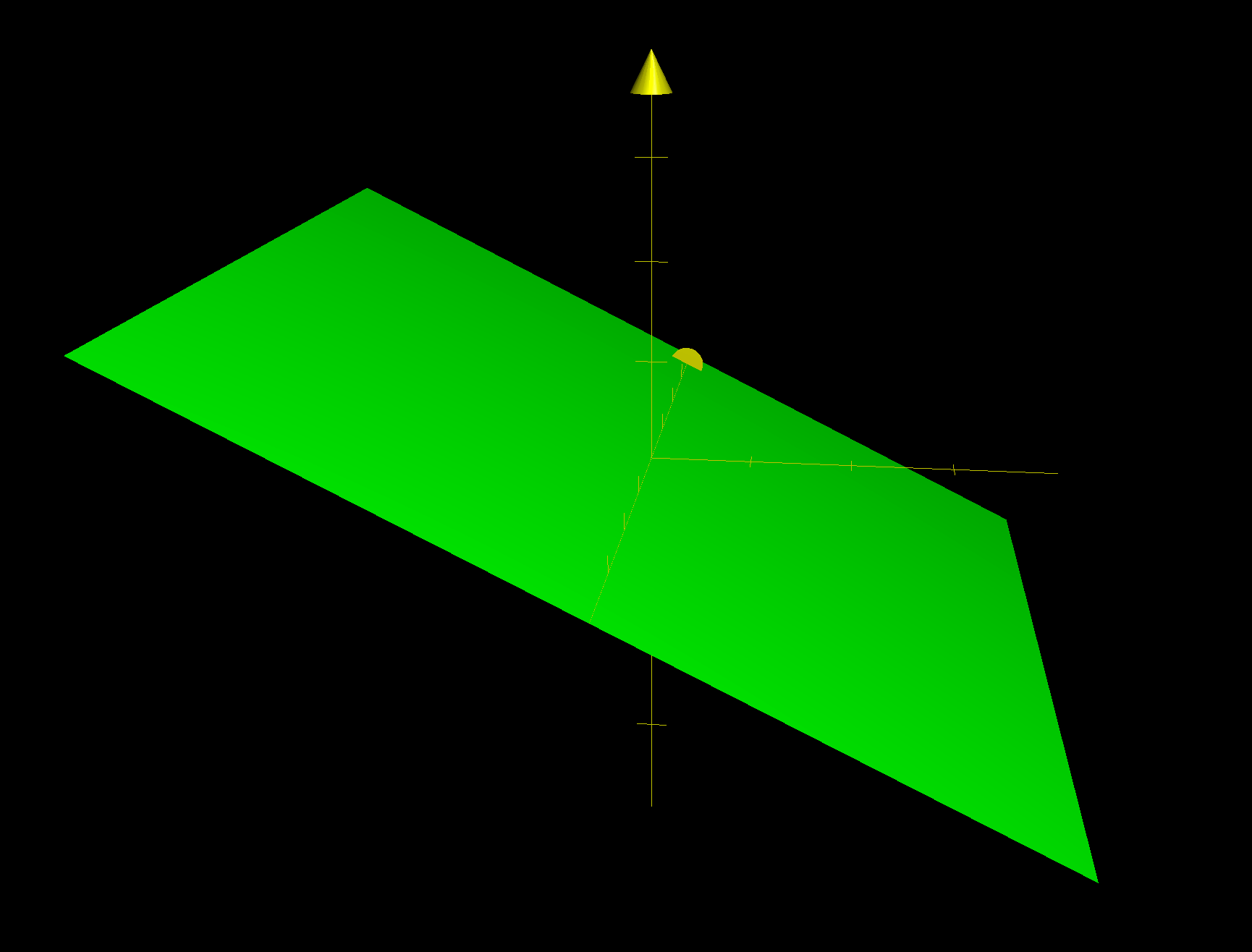

To translate this into maths, what we need to imagine is a hyperplane given by something like the following:

\[cz = y\]Where \(c \neq 0\). This can be seen graphically (with \(c = 2\)) here:

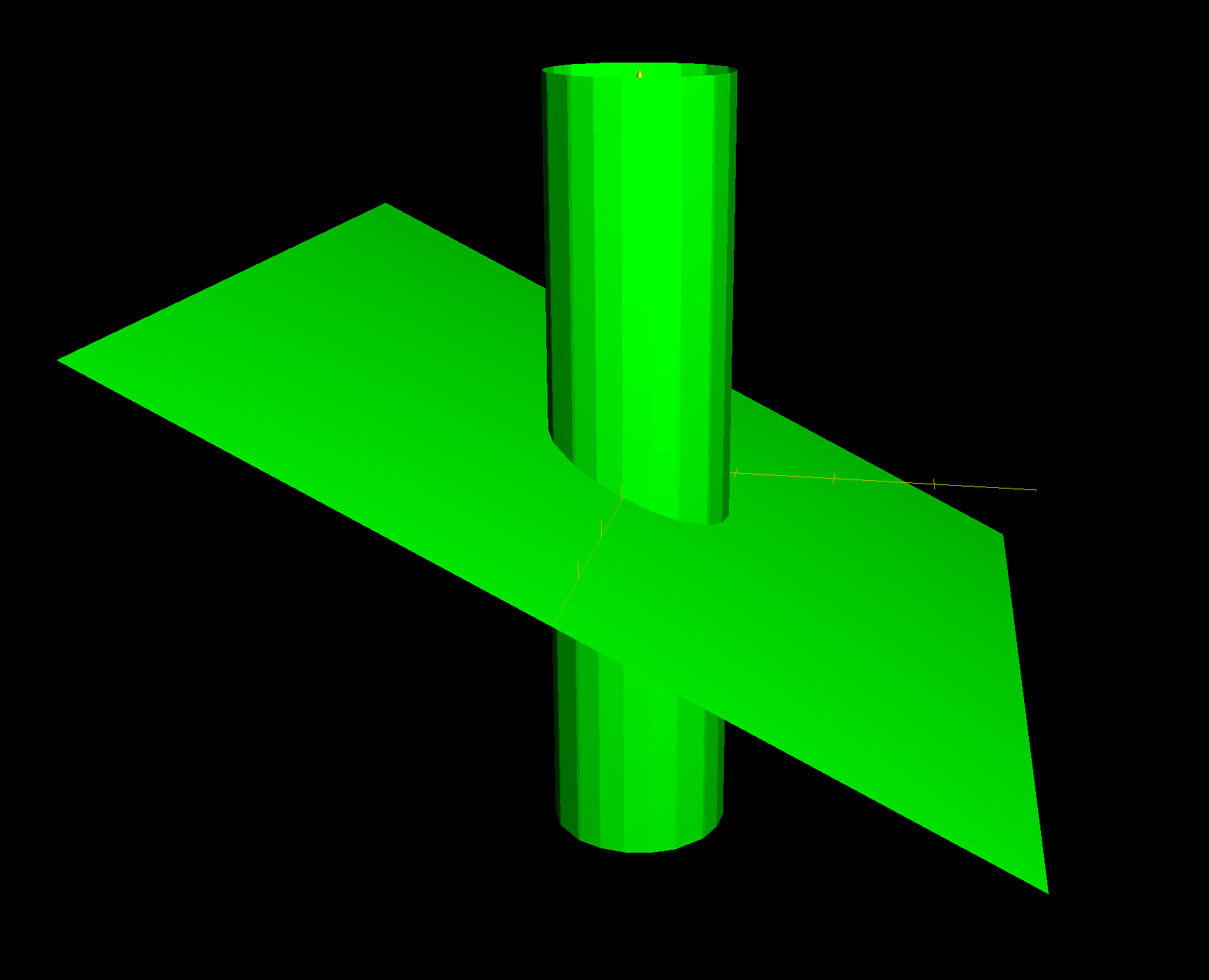

If we picture both the cylinder and the plane, we can start to imagine how their intersection would form an ellipse:

However, it is important to see that if we substitute \(y\) in the equation for the cylinder with \(cz\) we would get something like the following:

\[\frac{x^2}{r^2} + c^2\frac{z^2}{r^2} = 1\]This is actually an elliptic cylinder! It would look like the following:

But we should note that the elipse formed on the \(x-z\) plane is nothing more than the projection of the ellipse we’re actually looking for onto the x-z plane. In fact, in the special case of \(c = 1\), we would get a circle, which, as we will see shortly, is actually the projection of the following ellipse onto the \(x-z\) plane:

\[\frac{x^2}{r^2} + \frac{z^2}{2r^2} = 1\]To solve our problem it would be easier to parametrise both our cylinder and our plane as follows 4:

\[x = r\cos(\theta)\] \[y = r\sin(\theta)\] \[z = y\tan(\alpha)\]Where \(\alpha\) is the angle formed between the hyperplane \(cz = y\) and the \(x-y\) plane, so, for instance, if \(c = 3\) (as in our example) \(\alpha = \frac{\pi}{8}\).

This is already our wanted ellipse, it just doesn’t look like it still. What we need to do is rotate the whole space around the \(x\) axis with an angle of \(-\alpha\). The rotation would look as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} \begin{bmatrix} x \\ y \\ z \end{bmatrix} & \mapsto \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \cos(-\alpha) & -\sin(-\alpha) \\ 0 & \sin(-\alpha) & \cos(-\alpha) \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} x \\ y \\ z \end{bmatrix} \\ & = \begin{bmatrix} x \\ y\cos(\alpha) + z\sin(\alpha) \\ -y\sin(\alpha) + z\cos(\alpha) \end{bmatrix} \end{aligned}\]So, applying this rotation to our parametrised curve, we get the following:

\[\begin{aligned} \begin{bmatrix} r\cos(\theta) \\ r\sin(\theta) \\ \sin(\theta)\tan(\alpha) \end{bmatrix} & \mapsto \begin{bmatrix} r\cos(\theta) \\ r\sin(\theta)\cos(\alpha) + r\sin(\theta)\tan(\alpha)\sin(\alpha) \\ -r\sin(\theta)\sin(\alpha) + r\sin(\theta)\tan(\alpha)\cos(\alpha) \end{bmatrix} \\ & = \begin{bmatrix} r\cos(\theta) \\ r\sin(\theta)\cos(\alpha) + r\sin(\theta)\frac{\sin^2(\alpha)}{\cos(\alpha)} \\ -r\sin(\theta)\sin(\alpha) + r\sin(\theta)\sin(\alpha) \end{bmatrix} \\ & = \begin{bmatrix} r\cos(\theta) \\ r\frac{\sin(\theta)}{\cos(\alpha)} \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{aligned}\]Therefore, what we end up having is the ellipse given by:

\[x = r\cos(\theta)\] \[y = r\frac{\sin(\theta)}{\cos(\alpha)}\] \[z = 0\]This is the ellipse we were looking for! 🎉 Only now it’s been rotated into the \(x-y\) axis, so we can now use the standard equation for an ellipse:

\[\frac{x^2}{r^2} + \cos^2(\alpha)\frac{y^2}{r^2} = 1\]This means the semi-major and semi-minor axes, \(a\) and \(b\), would be given by, \(r\) and \(\frac{r}{\cos(\alpha)}\), respectively.

If we assume (as it was mentioned earlier) that \(\alpha = \frac{\pi}{8}\), then we can calculate, for a given ring size, the circumference that the corresponding ellipse would have.

For a specific example, take the ring size of 9 (US). Its diameter is 18.95mm, so \(r = 9.475\). Therefore \(r = 9.475\) and \(b = \frac{9.475}{cos(\frac{\pi}{8})} \approx 10.364mm\). Using an ellipse-circumference calculator (like this one), we get that the required circumference for the ellipse is 62.389mm.

🍀